10. Conservation/Restoration of Biological Material in Contemporary Art: A Perspective from Academia in Collaboration with Artists

- Ana Lizeth Mata Delgado

Since 2004 the Seminario Taller de Restauración de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo (Workshop-Seminar on Restoration of Modern and Contemporary Art) offered at Mexico’s Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRyM), which is part of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Historia (INAH), has positioned itself nationally and internationally as an academic space that researches, conserves, restores, and documents new artistic proposals created in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The workshop-seminar was created in 2001 in response to in-depth reflections on new professional challenges facing ENCRyM’s graduates with bachelor’s degrees in restoration. New artistic production techniques and new vocational opportunities outside INAH in both the public and private spheres also influenced its creation. The workshop-seminar is presently being offered in the ninth semester of the bachelor’s degree program as a full-time, on-site elective. At this time it is the only course of its kind in Mexico; none of the other schools or universities currently providing a bachelor’s degree in restoration offer courses that address cultural issues in an integrated manner. Its uniqueness attracts students outside of ENCRyM to take the course to supplement their training.

Over the course of its fifteen years so far, distinct methodologies have been developed in the workshop-seminar for addressing issues in the conservation and restoration of artworks made from organic and inorganic material. This paper addresses only the cases of art made from organic material. These methodologies consider different fundamental aspects—for instance production techniques, context of creation, context of exhibition, artist/creator, compatibility and interaction of materials, and existing as well as possible future dynamics of deterioration—to establish the best course of intervention. A primary consideration is collaboration with the artist in order to understand the meaning of the work, the artist’s intention behind using a specific material, and their long-term vision for and opinion on the work’s conservation.

Within the structure of the workshop-seminar’s academic program are three research projects: documenting, registering, and experimenting with materials in organic or inorganic contemporary art; conserving, registering, and documenting urban art and graffiti; and conserving and researching plastics. The first of these involves close collaboration with the creators of contemporary artworks in order to record their testimonies, which serve as vital documents for the conservator’s task, and experimenting with different substantive raw materials.

A distinctive aspect of this project is collaboration with artists to experiment mainly with biological material in the creation, conservation, and restoration of works of art. Examples of such collaboration have included works made with leather and pigs’ feet, others made with eggshells, and yet others crafted with coconut and maize fibers—a diversity of materials that reveals the creators’ ongoing search to innovate and produce works with different perspectives, which in turn also generates new problems and research urgencies vis-à-vis their conservation.

It is important to mention that artists are increasingly open to and interested in collaborating with conservators, and this dynamic paves the way for new research into both the constituent materials and new materials and strategies for conservation and restoration, thereby generating new, creative alternatives for proper conservation.

Conservation, Restoration, and Research on Works of Art Made from Organic Matter

As a result of the daily work within the workshop-seminar, and as part of the collaboration with artists such as Darío Meléndez, Grupo SEMEFO, Antonio Serna, Marta Palau Bosch, and Noemí Ramírez, to mention but a few, research projects have been conducted that have resulted in the conservation and/or restoration of works made with materials such as maize leaves, coconut fibers, animal skin, embalmed horse fetuses, and a taxidermied crocodile. For instance:

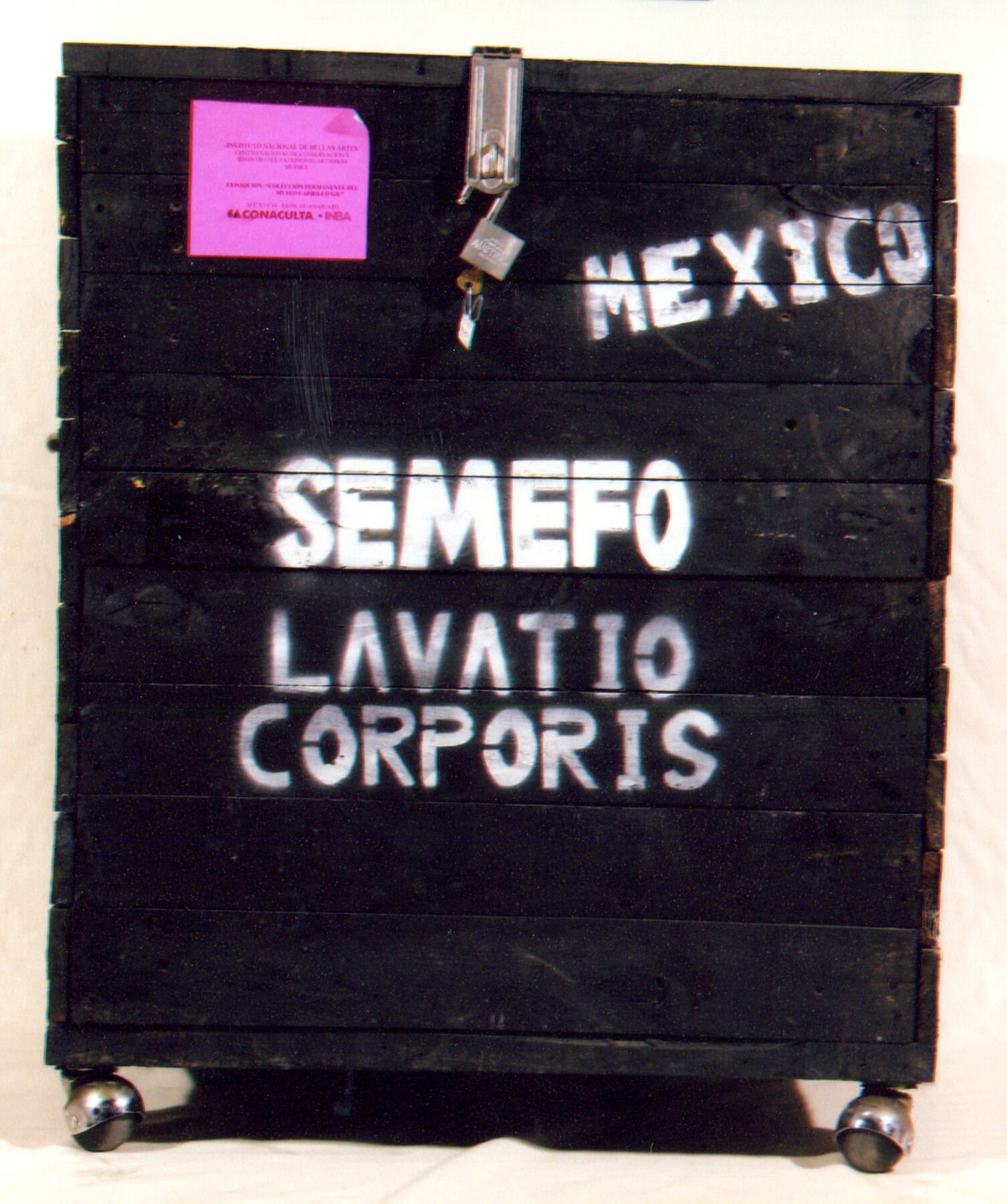

Grupo SEMEFO, Lavatio Corporis, 1994. Three embalmed horse fetuses on metal pedestals.

Antonio Serna, Untitled, 1984. Mixed media (oil, acrylic, mortar, pumice stone, and birdseed) on fabric.

Marta Palau Bosch, Mis caminos son terrestres XVII (My Paths Are Earthly XVII), 1985. Textile sculpture involving dyed henequen (agave) and totomoxtle.

Noemí Ramírez, Mirada del tiempo (Time View), 1985. Henequen, coconut, and palm fibers filled with wadding.

Teresa Margolles, Encobijados (fig. 10.1), 2006. Acrylic and polyester fibers with organic fluids, seeds, and adhesive tape, and T-shaped supports made of stainless steel. This work incorporates blankets used to wrap the corpses of victims of organized crime.

Taxidermied crocodile from a scientific collection, 1980s.

The research projects and interventions follow a process through which the researchers investigate the material and its meaning, and issues in conserving the work. They usually follow the following procedure:

1. Diagnosis of the Work of Art

Before the work is selected, it is assessed at its current site to determine whether it is an appropriate subject for the workshop-seminar. Collections normally considered for this are mainly in public museums.1 Once a diagnosis has been conducted on the state of conservation of the work, a project is created that identifies in detail the deterioration, options for conservation, scope of intervention, and any agreements required. Once both parties accept the initial agreement, the work is transferred to ENCRyM and its conservation and/or restoration begins.

2. Artist Interview

While assessing the specific work at hand, the research project investigates the artist’s broader body of work, processes, motivations, and materials. Guidelines are established and defined for an interview, which may focus on the work to be restored and/or the artist’s broader production. Usually, once an artwork is in the workshop, the artist is invited to visit and begin the interview process (fig. 10.2). To date, the workshop-seminar has a database of more than forty artist interviews, all focused on the conservation of their works and on conservation and/or restoration of modern and contemporary art in general. The information collected during the interview plays an important role in determining possible solutions for conservation; sometimes the artist has a specific opinion on the matter, which is considered and conveyed to the owner of the work (usually, as noted above, this is a museum or cultural institution).

Two particularly interesting interviews were with Darío Meléndez and Colectivo Sonámbulo. Meléndez’s Tilma Porca is an installation that uses pigskin in different presentations to reflect the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe (). Colectivo Sonámbulo’s Incontenible (Uncontainable) involved a research project for the purpose of evaluating and determining alternatives to slow the rotting of pigs’ feet ().

3. Scientific Analysis and Research

For the research and the interdisciplinary work, the team works at ENCRyM and/or in external laboratories, depending on the type of analysis required. Team members conduct biological, physical, forensic, and chemical analyses, depending on the issues present (fig. 10.3, fig. 10.4). Professors may contribute their expertise to answer questions posed by a particular artwork. When ENCRyM does not have the specialist required, external specialists are consulted who can provide supplemental information.

4. Evaluation of Conservation Alternatives

After an artwork’s state of preservation is assessed and diagnosed and the meaning and conceptual aspects of the work considered, different conservation options are proposed. The artist’s opinion, technical resolutions, technical and financial resources, viability of the processes, and aesthetic and artistic factors are all considered. This usually occurs after several weeks of working closely with the artwork and after obtaining all analytical results. Next steps include determining the scope, a time schedule, equipment and materials needed, and human and financial resource requirements.

5. Presentation of the Best Alternative

After assessing advantages and disadvantages of each proposed conservation process, a meeting is held with the custodians of the work in which findings and recommendations are presented. This includes general information, research done on production techniques, material and scientific analyses, state of conservation and diagnosis, graphic and photographic registry, the interview with the artist, and the artist’s opinion. Based on this presentation, a consensus is reached between the museum and the restoration team, and formalized as an agreement.

6. Intervention

Having established the scope, processes, materials, and agreement(s) among the parties, conservation and/or restoration begins. It usually lasts from four to eight months, depending on the type of work and the issues involved. This intervention is usually conducted in the workshop-seminar facilities at ENCRyM (fig. 10.5, fig. 10.6).

7. Delivery of Results and Work Report

When all restoration work is complete, an exhaustive report is delivered to the museum, to the ENCRyM library, and sometimes to the artist, containing all the information concerning the work, from the start of the registration to the research, analysis, and actions carried out, plus a complete photographic record of the intervention. This document aggregating all the relevant information is now a unique file on the work that will serve for future research and/or intervention (if necessary).

8. Dissemination in Specialized Forums and Publications

Last, the research and work conducted are disseminated and circulated in various academic forums: conferences, lectures, symposia, and written articles.

Case Study

Grupo SEMEFO’s Lavatio Corporis is a useful case study to illustrate the methodology explained above. This installation involves three embalmed horse fetuses placed on metal pedestals. These are part of a series of five installations exhibited in four galleries of the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, in 1994 (). Although, in this case, the work that was restored was not the original piece (the first version decomposed as a result of excessive humidity), the piece we worked on is authentic in conceptual and material terms; Grupo SEMEFO created a new version within the same year and with the same characteristics, which it donated to the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil.

This work came to the workshop-seminar in 2010 as a result of its conservation issues, which consisted mainly of material and aesthetic changes. Interestingly, it was not initially clear whether these contributed to or detracted from the piece’s meaning. The material state of the work indicated that, without intervention, in would likely continue to deteriorate and perhaps be lost, yet this was potentially congruent with the concept proposed by the artists. It is a processual work whose deterioration is intrinsic to it.

Two main condition issues were observed. Lavatio Corporis was in fact at that time mostly materially stable, but the fetuses were noted as having reduced density due to loss of bodily fluids, as well as desiccation and contraction of the tissues. There was also a loss of flexibility to the skin and resulting parchment-like texture caused by progressive desiccation and polymerization of the proteins structurally modified by the embalming process. The pedestals were neither original nor stable in supporting the fetuses. Additionally, the storage box was moldy and without any ventilation, such that mold continued to attack the fetuses.

Several scientific analyses were performed, including examination of the fetuses under UV light, analysis of the skin and the threads suturing the wounds inflicted during taxidermy, and incubation of a mold culture in the box and on the fetuses to determine the best way to eradicate it. Generally speaking, three possible options for conservation presented themselves:

The ephemeral work: the work will eventually be lost thanks to the decomposition in which it is engaged. In this case, a record would remain of the work’s existence and transformation.

The permanent work: conservation and/or restoration treatments and resources will be used to achieve permanence of the work.

The renewable work: when the fetuses have deteriorated to an agreed-upon degree, the organic components will be replaced with fetuses deemed equivalent, but newer.

After interviewing Grupo SEMEFO, it was determined that the fetuses’ current state of deterioration was central to the work’s meaning. It was therefore deemed essential to make conservation efforts to stabilize its present appearance, and so the second option was chosen. The pedestals were replaced, and the storage box and fetuses were fumigated to kill the mold (fig. 10.7, fig. 10.8, fig. 10.9).

The piece has great historical, aesthetic, and political relevance to the contemporary art of Mexico, representing a historical period and art movement that explored specific discourses and means of expression. There was a collective consensus at the time the installation was donated that the museum would provide for its long-term conservation and maintain its permanence. Any ephemeral consideration was superseded. Over time, that characteristic has nourished the work’s discourse, making it an example of the fact that institutions, museums, and galleries house not only works but, in some cases, processes as well (, 54).

Conclusions

Material experimentation in art opens new perspectives and poses challenges for conservation and restoration, so it is essential to develop strategies aimed at better solutions to issues presented in conserving art made from organic matter. Direct interactions between artist and restorer are becoming increasingly relevant in the conservation and restoration of contemporary art, in the interest of both creating new works of art and conserving existing ones. Exchanges of knowledge and experience lead to a better understanding of certain works and their meaning and function, as well as future conservation efforts. Documentation through interviews, notebooks, archive materials, and reports serves not only as testimonies concerning conservation work, but also as background for future research.

Note

We have worked with the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City; Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City; and the Museo Regional de Nayarit, Tepic. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Ganado and Herrera 1994

- Ganado, Edgardo, and Carolina Herrera. 1994. “SEMEFO, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil. Catálogo de Exposición.” Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. Mexico City: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Alvar and Carmen T. de Carrillo Gil.

- López Guzmán 2010

- López Guzmán, Javier. 2010. “Informe de los trabajos de conservación sobre la obra: Lavatio Corporis / Grupo SEMEFO.” Seminario-Taller de Restauración Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo. Temporada de trabajo agosto-diciembre 2010. Unpublished.

- Meléndez and Mata Delgado 2012

- Meléndez, Darío, and Ana Lizeth Mata Delgado. 2012. “Tilma Porca.” In Memorias del 5º Foro Académico, edited by ENCRyM, 33–40. Mexico City: ENCRyM-INAH. Available at https://www.repositoriodepublicaciones.encrym.edu.mx/pdf/4-TilmaPorca.pdf.

- Rebolledo et al. 2019

- Rebolledo, Karla, et al. 2019. “Incontenible: entre la creación artística y la conservación.” Estudios sobre conservación, restauración y museología 5:157–70. Available at https://www.repositoriodepublicaciones.encrym.edu.mx/pdf/13%20incontenible_corregido2019.pdf.